SMOOSH JUICE

RPG Evolution: If It Kills, We Can Build It

In traditional D&D dungeons, traps are everywhere. But what keeps them running?

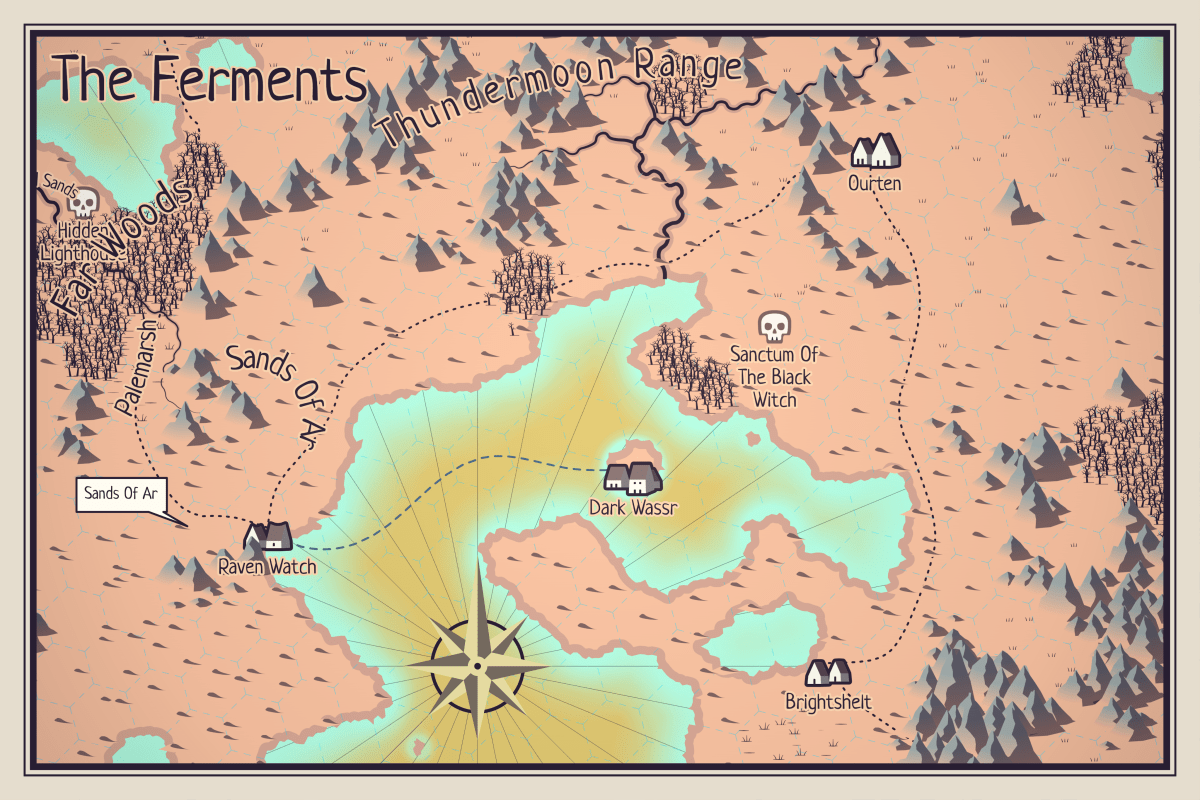

In the world of Dungeons & Dragons, dungeons are often steeped in magic, with traps triggered by unseen forces and monsters appearing from thin air. But what if we approached these subterranean labyrinths with a different lens, one that emphasizes the mechanical underpinnings of this fantasy world? What if traps weren’t just magical inconveniences, but cleverly designed contraptions with understandable mechanics? Embracing a mechanistic approach to dungeoneering can fundamentally change how players interact with the environment, turning them from passive victims into active problem-solvers … and potentially resourceful engineers.

A Mechanistic Approach to Dungeon Design

A mechanistic approach implies that there’s an internal logic to how the dungeon works. It’s not just there, it’s set up as an obstacle with an intelligence behind it. This requires a few fundamentals that are typical of dungeon tropes, known as the “Durable Deathtrap:”

Our adventure heroes enter some ancient ruins in search of something important or valuable. Although the site may have lain undisturbed for centuries or even millennia, the place is filled with a variety of lethal, fully functional traps left behind by the previous occupants. Said traps are often Bamboo Technology considerably more complex than anything else the creators were capable of making. Even more remarkable is the fact that they have not decayed at all, even if the environment is one that should require extra maintenance, and are just as lethal as they ever were, let alone the fact that any poisons should have decayed centuries ago. Projectile traps might even be capable of reloading themselves an indefinite number of times.

Assuming these traps aren’t entirely magical in nature, the first foundational element to create a mechanistic dungeon is some level of technological advancement. This doesn’t necessarily mean laser guns and robots; it could manifest as a form of bamboo tech, utilizing intricate systems of gears, levers, counterweights, and cleverly shaped stone to create functional traps, as hinted at in Raiders of the Lost Ark with its elaborate mechanisms. Alternatively, a more overt steampunk aesthetic could allow for clockwork devices and steam-powered mechanisms within the dungeon. This technological basis allows for traps that aren’t purely magical but have tangible, repeatable effects.

The second crucial element is internal consistency. If traps are mechanical, they should (within the fantastical logic of the game world) operate according to consistent principles. PCs should be able to observe, deduce, and potentially even predict how these traps work. This consistency rewards careful observation and logical thinking, turning encounters with traps into engaging puzzles rather than random occurrences.

The most extreme example of this are Grimtooth’s Traps as described by Brandes Stoddard:

Especially in the 1e era, another approach to traps also appears, in the works of the incomparable and bizarre Grimtooth, by Flying Buffalo. Grimtooth’s traps are famously elaborate, ridiculous, and unfair – the latter of which may be a reasonable tactical decision for the defenders, but is a terrible gameplay decision on the GM’s part. Still, convoluted traps that endanger the whole party are not all bad – everyone is invested in and able to contribute to finding a solution. In Grimtooth’s works, the insane deathtraps are often obscure, guess-what-I’m-thinking physics challenges.

Whatever model you choose, it means that there is a logic behind traps that can be guessed (well not always in Grimtooth’s case, but sometimes). Once the model of your dungeon’s secret workings has been laid out, then it’s time to power it with some sort of resource.

Who Resets Those Traps?

Powering traps takes some sort of energy. As pointed out in the “Durable Deathtrap” trope above, if it’s not potential energy liked coiled springs or magically-replenishing resources, it’s likely someone or something keeping those traps functioning. For an example of how that might work, the video game series Dungeon Keeper provides a model.

In Dungeon Keeper, the player takes on the role of an evil overlord constructing and defending their dungeon. Crucially, the game posits an entire ecosystem dedicated to this purpose. Imps, the player’s primary minions, are responsible for mining resources, constructing rooms, and building traps.

Traps in Dungeon Keeper aren’t just placed and forgotten. They require construction in a workshop, and Imps will actively fetch the necessary components. Many traps also have a limited number of triggers before they need to be reset or replaced by the Imps. This implies a hidden logistical network within the dungeon, with resources being gathered, traps being manufactured, and maintenance being performed by a dedicated workforce.

Trap “keepers” in D&D can range from kobolds (known for their trap-making skills) to tireless creatures like golems or undead. The point is that there’s an underlying infrastructure that supports the existence of complex, mechanical traps. And once PCs figure it out, they can counter or even co-opt it.

Ingenuity in Action

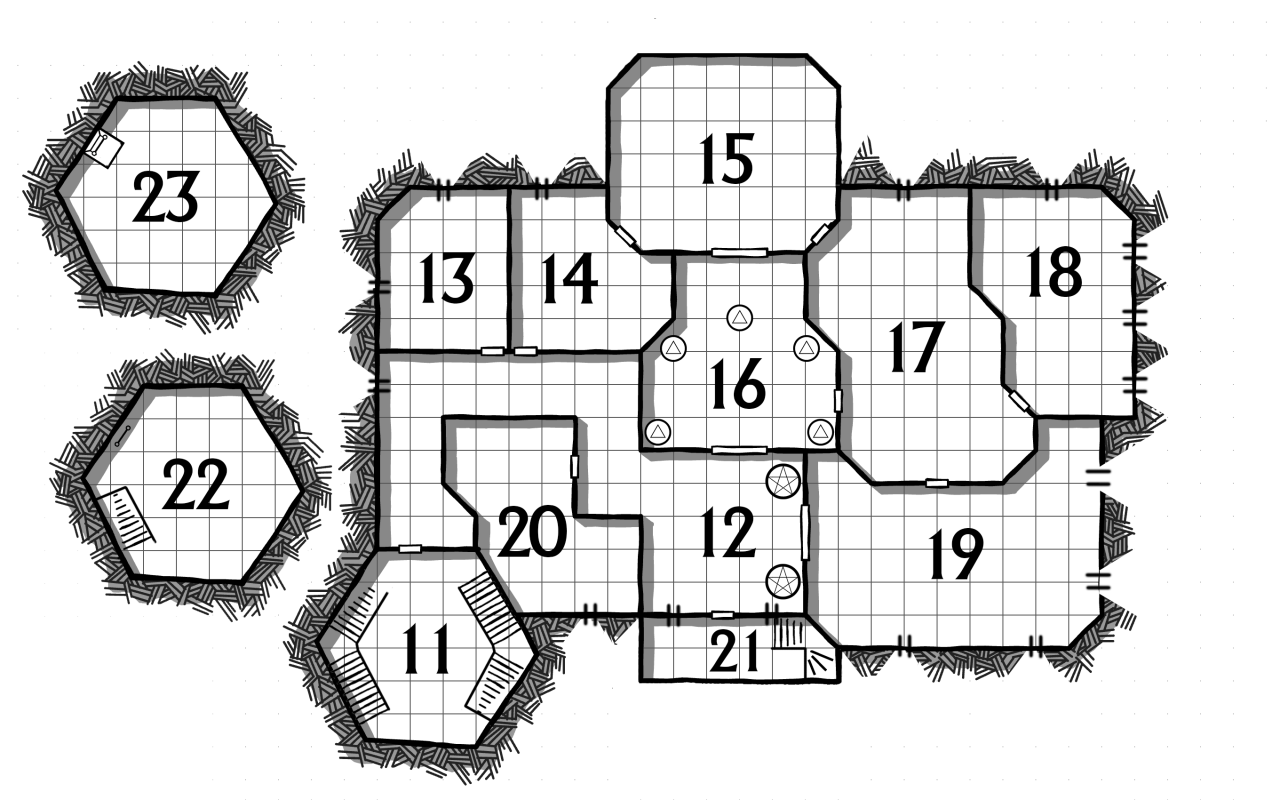

The second episode of the anime Delicious in Dungeon, titled “Roast Basilisk/Omelet/Kakiage,” illustrates how a mechanistic understanding of a dungeon can empower adventurers. The halfling rogue Chilchuck is a master of traps, a skill initially underestimated by the dwarf warrior Senshi. However, Senshi quickly comes to appreciate Chilchuck’s expertise as they begin to leverage the dungeon’s existing traps for their own benefit, specifically for cooking.

In this episode, a swinging axe trap, designed to deter intruders, is ingeniously repurposed to chop up a giant bat they had defeated earlier, saving valuable time and effort. Furthermore, they discover a fire trap, not fueled by magic but by oil. Recognizing this mechanical component, they cleverly drain the oil to use it for deep-frying a delicious kakiage (a type of fritter) made from mandrakes and basilisk meat.

This is just one example of how PCs, once they figure out how a thing works, can use it to for their own ends. The obvious use case is to leverage traps against other monsters they might encounter, but in the example with Chilchuck and Senshi, it helped them prepare food they would normally never be able to cook (as Marcille the elven mage points out, it’d be much harder to deep fry food at a consistent temperature over a campfire).

Rewiring Your Dungeon Delving

Dungeons don’t have to make sense, and often the easiest approach for DMs is to simply claim it’s a magical effect. But even then, magical effects are part of D&D’s rules system — that is, there are snare and alarm spells that can be observed and potentially dispelled. With enough internal logic, understanding a trap is as important as avoiding it, and potentially moreso if it means players gain knowledge they can apply elsewhere.

Encouraging players to see traps not just as damage dealers but as intricate mechanisms can lead to moments of brilliance. When designing your next megadungeon, consider the technological basis for its traps and the internal consistency of their operation. And potentially, the little guys who keep it all running, like the small but mighty Tucker’s kobolds.