SMOOSH JUICE

Dungeons & Heroquests

RuneQuest is not the only game I play, despite all the time I have spent writing about it and for it. Call of Cthulhu has always been a favorite of mine, and I have a scenario for it in the upcoming campaign, The Sutra of the Pale Leaves. I’ve written here, here, and here about my love for Nephilim, and here about Pendragon. And those are just the Chaosium games. I’ve blogged about my campaigns for Numenera and The Dracula Dossier, and reviewed tons of other games, including Vampire, Old Gods of Appalachia, Spire, Kult Divinity Lost, Vurt, Nobilis, and so on. RuneQuest and I have just been a bit stapled together since Six Seasons in Sartar appeared, and I am good with that.

Like so many Gen X brats, I actually started playing RPGs with Dungeons & Dragons. I was in the 5th grade and drafted into my public school’s GATE program, mainly because I was that mutant species of weird kid who spent all his time alone writing stories. The school psychologist, who ran the program, had read in a journal about a professor of neurology who had just revised and written a new edition of D&D, John Eric Holmes. Holmes asserted that the game taught communicative and critical thinking skills, and was a way for pre-adolescents to exercise social, math, and creative abilities. So she bought a set, and assigned me the task of reading it and being the Dungeon Master for the other kids in the program. Ironically, the same school district that introduced me to RPGs would ban them just a few years later as the political winds shifted and the Satanic Panic reared its shaggy head.

I ran D&D throughout the 5th and 6th grades, expanding into the Moldvay and Cook Basic and Expert sets, and then the eldritch dweomercraft of the High Gygaxian AD&D trilogy. It wasn’t until I arrived in junior high school, and joined the “D&D club,” that I was informed they were playing something called RuneQuest. That was the end of D&D for me. Sort of. I would later run a little of 2nd edition AD&D, and the same copy of the Rules Cycopedia that I bought in the college book store in 1991 still sits on my shelf now. But RuneQuest, Chaosium’s other titles, and an ever-expanding circle of RPGs kept me occupied for decades.

When I did peek in on post-2000 D&D it was a game I no longer recognized. I am not saying it was bad or that earlier editions were better—I don’t really have a dog in that fight–but the game increasingly had more to do with Star Wars, video games, Japanese anime, and the MCU than it did with the survival horror, Conan/Elric/Fafhrd-inspired sword and sorcery game I used to run. I was, however, intrigued by the rise of the retro-clones, games like OSRIC, Labyrinth Lord, and Swords and Wizardry, which attempted to keep older editions of the game alive. As this bloomed into the OSR (another rabbit hole I don’t want to meander down here), with games like Lamentations of the Flame Princess, MÖRK BORG, and ShadowDark, I found myself playing them, revisiting dungeons once again (more on the OSR and these games here).

I say all this because in my recent running of dungeon crawls once more, alongside my continuing RuneQuest campaigns, I have noticed something I hadn’t noticed before.

Dungeon crawls are heroquests, and heroquests are dungeon crawls.

Let Me Explain

Right now you are probably asking “what the deuce are you on about, Montgomery?” I’d wager the wording is a bit different, unless you actually are a 19th century upper class Brit, but that general sort of question.

As per Cults of RuneQuest, Mythology, a heroquest is “a direct interaction by mortals with the divine realm of myth and archetypes…participants enter the realm of legend and myth to interact with heroes and gods, gambling precious life force to gain miraculous powers and bring back magic” (p. 14). In other words, adventurers leave behind the world they know, enter a shadowy otherworld known only through stories and legends, to risk their lives and bring back wondrous treasures.

Sounds suspiciously like a dungeon crawl to me.

“The Shadowdark,” Kelsey Dionne tells us, “is any place where danger and darkness hold sway. It clutches ancient secrets and dusty treasures…daring fortune seekers to tempt their fates…if you survive, you’ll bring back untold riches plucked from the jaws of death itself” (ShadowDark, p. 7). In other words adventurers follow stories and legend into the unknown, into a lost world strange and dangerous, where they are tested. If they survive, they bring back wonders. If there is any real distinction between that a heroquest, it is one of degree and not of kind.

The line gets even blurrier when you stop and consider what a fantasy RPG dungeon is… it’s the underworld, one of the oldest archetypes of the Other Side there is. Journeys by heroes into the underworld are so common we have a name for them, “katabasis.” In classical mythology, the ability to enter the underworld and return is the very definition of a hero. Aeneas enters the underworld seeking knowledge of the future. Ovid describes Juno descending into underworld, reminding us of Inanna/Ishtar doing the same. Ovid also famously describes Orpheus entering the underworld to try and bring back his dead wife Eurydice, as did Indra to bring back the Dawn (also the goal of Orlanth and the Lightbringers). Heracles enters the underworld as his 12th labor, Pwyll entered in Welsh mythology, and so on. We can argue that the Shadowdark (my new favorite term for the fantasy dungeon) is not literally the world of the dead, but it is a lightless realm where death waits. Even the grandfather of all RPG megadungeons, Tolkien’s mines of Moria, blur the line between mundane and myth. In those lost halls the fellowship encounters the Balrog, “a demon of the ancient world,” a mythic divine being, and against it Gandalf falls only to return from the dead, much as Jesus did after his descent into hell.

Again, differences of degree, not of kind.

Old Tools, New Uses

As I started replaying old school dungeon crawls alongside RQ, it started to change the way I ran and constructed heroquests. In both Six Seasons in Sartar and The Company of the Dragon, I presented rules for heroquesting. But by the time I wrote a full heroquest chapter for The Seven Tailed Wolf, something had changed.

I had added a map.

I had gotten into the habit by then of making maps for my OSR games, something I have always found immensely stimulating to do. And doing this drives home the difference between a dungeon crawl and a story-oriented game. The latter is a linear thing, in which scene 1 is followed by scene 2, then scene 3, and so on. The characters are simply moved down the line through each. The pejorative term is “railroading.” But in the former, each room of the dungeon is, in fact, a “scene.” It has a setting, it has characters (NPCs and monsters), it has challenges and stakes. The crucial difference is that it isn’t linear. Whether you turn right or left decides whether you walk into the goblin lair or down the hall with the pit trap. Both are scenes, but this time the adventurers have to make a choice and those choices have genuine consequences. Pick the southern passage and you stumble right into the lost shrine of the relic you were seeking. Just fight the final boss and it’s yours. Go north or west, however, and you encounter a half a dozen other scenes, wearing you down, making the final boss encounter–if you even live to arrive at it–all the harder.

In The Seven Tailed Wolf I introduce the myth of the founding of the Haraborn vale. The Black Stag arrives at this mountain valley and falls in love with Running Doe. He proposes marriage, but she refused. The valley is the hunting ground of the Seven Tailed Wolf, and she will not marry and have children just for the Wolf to eat them. So the Stag vows to drive the Wolf off, and along the way (just as Dorothy Gale and Momotaro did) he meets others to aid him in his final battle.

This could be run as a story. Scene One, the characters meet Running Doe and vow to fight the Wolf off. Scene Two, they meet the Weaving Sister, and need to recruit her. Scene Three they meet the Night-Winged Bird. Scene Four, the strange hairless beast that walks upright. Scene Five they encounter the Hissing Wyrm, and so on.

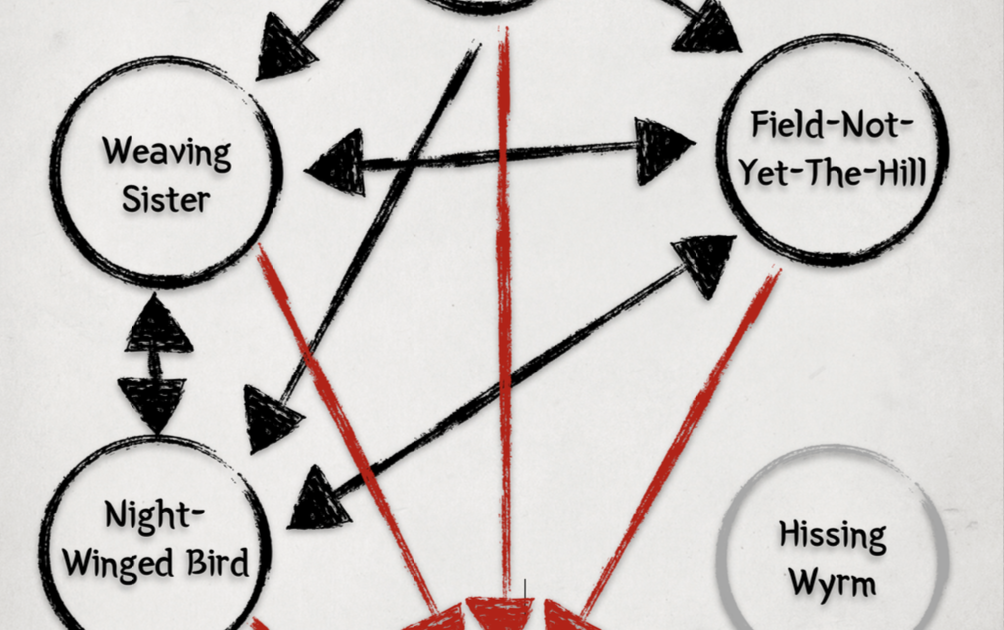

Yet it is all much more interesting if you throw away the linear script, and spread the scenes out like rooms in a dungeon. After they make their vow to Running Deer, what next? Do they seek out the hole where the Weaving Sister lives? Do they scale the high cliffs to find the Night-Winged Bird? Do they follow the stream to the Field-Not-Yet-A-Hill? Or do they simply go straight to meet the Wolf head on, not bothering with allies? They have options now, and they have agency. Their choices shape the narrative.

And that is all fairly simple. Old school games had tons of dungeon building tools that can make heroquests more interesting.

For example, think about the “secret door.” The Weaving Sister lives in the Riddle, a sacred Earth temple which earlier in The Seven Tailed Wolf we learn was the place where Ernalda would come to speak with her aunt, Ty Kora Tek. Here they would talk and sing songs to each other, Ernalda just outside the Riddle, Ty Kora Tek just within. Imagine setting up this up as a hidden scene. When encountering the Weaving Sister, if one of them sings into the Riddle into opens a new path into the Ernalda/Ty Kora Tek myth. There they can meet Ernalda and perhaps get additional magic to fight the Wolf… but only if they answer Ty Kora Tek’s riddles first. It is a separate myth, and has nothing to do with the Seven Tailed Wolf myth, but the Riddle links both. Maybe the adventurers never think to try singing into the Riddle and never find the other myth. That is fine too. It’s a secret door.

Another interesting notion is the “wandering monster.” When traveling from one scene to the next, they might encounter beings that have nothing to do with the myth they are exploring. Maybe they find a party of other heroquesters, and now either have to ally with them or compete. Maybe they come across beings from other stories, Broo from the Devil’s legion, the dead who are wandering lost an aimless, etc. Setting up a random encounters table appropriate to the Age the adventurers are exploring is a fun way to liven up the game.

Finally, don’t be squeamish about letting them get lost. The adventurers find a path up the mountain side, but it forks. Go right, and they eventually come to the Night-Winged Bird and are on the right track. Go left and they arrive at the Dragonewt nest of High Wyrm, and enter a draconic myth. Getting lost was a big part of old school dungeon crawls.

Mythology is a terrific resource for all of this, especially the Mythic Maps. Imagine the adventurers are in the Golden Age, pp. 86-90. They are seeking Aldrya’s Tree. While crossing the Yellow Forest their choices might take them to Oslira who has already been tamed and redeemed, or face-to-snout with Sshorg the Blue River, itching for a fight. These are neighboring locations on the map, and two very different scenes.

So the next time you are running a heroquest, trying drawing an old school map of it first. Be devious. Give it lots of choices and directions, dead ends and wrong turns. Detail each scene like you would stock the room of a dungeon, then let the dice roll and the games begin.